How do MET make their helmets?

Ever wondered how a MET (from helMET in case you were wondering) helmet is made? We went to the company’s Italian headquarters to find out…

Founded on the shores of Lake Como, Italy in 1987 by Lucianna Sala and Massimo Gaiatto, the MET helmet factory now sits in the heart of the Alps in Talamona. The state-of-the-art facility is capable of producing 3,000 lids a day.

MET pride themselves on the fact they design and manufacture helmets on one site, enabling them to innovate and develop new products much more quickly than their counterparts.

Birth of a lid

Each new helmet begins life on a computer screen, where the shape and venting is designed. Exhaustive testing on every new model is carried out before any physical helmet is made.

Structural impact simulation testing is done to find any weaknesses, and geometry modifications can be made following 3D computer model testing.

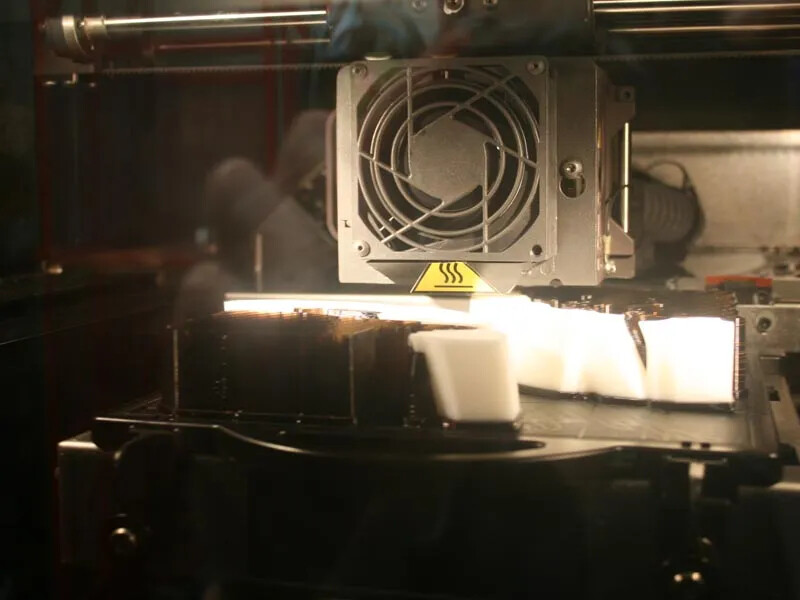

Once the helmet has passed this stage, a 3D printing machine is put to work and creates a life-size model of the helmet.

To the production line… and the robots

When the helmet gets the go-ahead, it can be produced in bulk in the company’s own factory.

The outer shell of each helmet is created from a polymer sheet which is heated and then blow-moulded.

The most impressive part of the helmet manufacturing process comes next – the robots! The outer shell is placed on the mount in the robot station, where each robotic arm has been pre-programmed to make a series of cuts.

The robot then gets to work, using a fine drill bit to cut the venting holes, strap anchors and any other incision needed on each helmet with absolute precision. The completed shell is removed from the mount, ready for the next process.

Any waste from this stage is recycled and turned into, among other things, coat hangers – it’s MET’s aim to be as environmentally friendly as possible.

Poly injection

The next stage in the manufacturing process is to fill the shell with polystyrene – the stuff that will protect your head if you hit the deck. The polystyrene is melted and injected inside a large machine, and the shell is then cooled with water. This is later recycled and used in the building’s toilets. After three minutes, the helmet comes out of the machine and is ready to be tested and finished.

Rigorous testing

MET distribute their helmets worldwide, and the headwear must conform to the standards of each country it is sold in.

All testing is carried out in the on-site laboratory using a range of punishing apparatus. The machine we were shown simulates a 60mph crash onto flat ground. There’s another anvil they use to simulate hitting the corner of a pavement.

It was clear from the demonstration we saw and all the tested helmets on display that the testing is meticulous.

Strap me up

Once tested and built, the final helmet is ready for the addition of straps, peaks, stickers and anything else.

How long will my helmet last?

There are many theories regarding when you should replace your helmet – which is why MET decided to answer the question by testing their own models. And the result? For eight years a MET helmet will do its job just fine, as long as you don’t damage it in a crash.

Why are top-end cycle helmets so expensive when they have less material in them than cheap ones?

Because high-end helmets like MET’s new Sine Thesis have less material (polystyrene) in them, they’re more aerodynamic, will keep your head cool more efficiently and will be lighter.

The process of creating a top-end helmet is far more time consuming, intricate and requires more energy than producing a cheaper model, as we found on our visit. More venting on a helmet requires more cutting and therefore more time, which equals more money.

A low-end model can be created in mass quantities using a mould which is capable of producing helmets six times as fast as a £134.99 Sine Thesis, for example. The Sine Thesis has a more complex design and therefore needs more time and attention paid to it.

The production process for each helmet is the same, however. “We combine all features in every helmet: first safety, then design, then ventilation,” said product manager Matteo Tenni.

Post time: Nov-05-2024